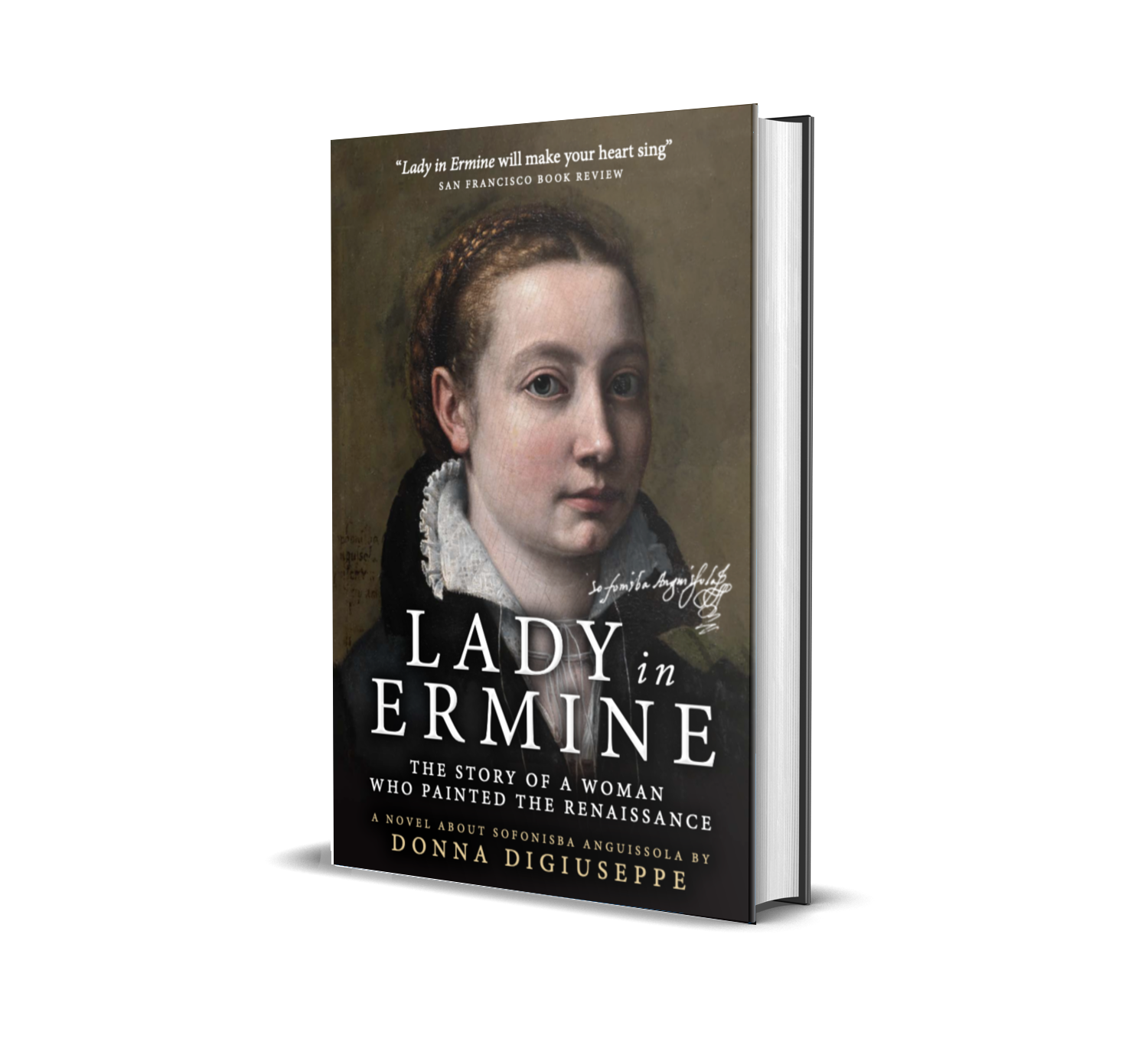

The story of Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1535-1625)

Chapter 31 Anthony van Dyck: Sicily 1615-November 1625

Sofonisba Anguissola is buried at The Church of the Genovese, Palermo Sicily.

A PRINCESS OF PEACE for 2021

So much pain, in so many ways, 2020. Yet, also, transformation, change, growth. Quarantine offered time and simplicity.

I used my time and angst in 2020 to polish the screenplay adaptation of LADY IN ERMINE.

Six rewrites. It was rough in June. Wordy in July. Rambling in August.

In September, I worked with Mira Kopell (UC Berkeley, Film & Media). Thank you, Mira!

October to nail the structure.

November, it all came together.

December, my gift to myself was to finish it.

From reader feedback, Ferrante Anguissola, and my own gut feelings, I know LADY IN ERMINE will make a beautiful film. Plus, historical fiction is back (Bridgerton). Strong female characters are in (The Queen’s Gambit). The time for LADY IN ERMINE is here.

But 2021 needs both patience and a kick. We pine for the vaccine distribution. We need to get on with life.

So, I’m beginning the second novel of the Lady in Ermine series. Sofonisba influenced so much, and so many.

LADY IN ERMINE: The Story of a Woman Who Painted the Renaissance begins on September 21, 1549. I will work to finish a manuscript of A PRINCESS OF PEACE by September 21, 2021. Patience and a kick for 2021. Thank you to all who gave feedback on the first novel. It has been so positive! I am grateful. To a healthy and peaceful 2021.

I’m delighted to read of Genova’s successful near-completion of the bridge that collapsed so very recently, in 2018. It gives me a feeling of optimism, literally a bridge for the future, inspiring.

I can’t resist connecting the success of this modern-day project with Sofonisba’s life of creative invention (invenzione/inventione). Sofonisba and her husband lived in Genoa from 1580 to 1615 before transferring to Sicily. During her time in Genoa, she continued to innovate, to paint high and low, and to influence artists, some of whom followed her footsteps to the Spanish court to contribute to the Escorial and the Spanish Habsburg collection. Her work and her mentoring of the next generation (the way Michelangelo mentored her) were formative to the artistic, creative, dynamic life of Genoa in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Four hundred years later, that creativity can make your heart sing.

Just last week the Wall Street Journal published an article about hobbies and diversions and referenced Sofonisba’s Chess Game painted in 1555. WSJ spoke of the hobbies that entertained the nobility. What Sofonisba enthusiasts see in the painting is the ingenuity of her work and the subversive messages of female power embedded in the chess game they play and the facial expressions they make. This was not an image of mere diversion. It was feminist enlightenment, 500 years before the me-too movement. Chapter 4, Chess Game, Cremona 1555, Lady in Ermine: The Story of a Woman Who Painted the Renaissance.

Sofonisba was not shallow. Nor are her enthusiasts.

In honor of Sofonisba’s newly recognized accomplishments and the Prado exhibition of her work, I would like to present her Boy Bitten (drawn for Michelangelo) and her Girl Laughing next to each other to accentuate Sofonisba’s effort. She conceived of these close in time and the figures and positioning show how she experimented with subtle changes. Sofonisba truly was a master Renaissance painter like her mentor Michelangelo. (Chapter 5 of Lady in Ermine).

We are so privileged to recognize her talent and effort now.

In honor of Sofonisba Anguissola’s new-found celebrity, I wanted to place her Prado Portrait of Philip II alongside her Portrait of a Spanish Prince (San Diego Museum of Art).

Sofonisba did not know Philip as a young child, but perhaps she could envision him as one. As Giorgio Vasari says, Sofonisba had invenzione. Perhaps she envisioned the adult King Philip as he would have appeared as a boy, while employing green to represent his youth, his budding, his spring. The hat style is even the same in each painting, the King’s being a mature black and the Prince’s being in youthful green. The painting is inscribed in Latin “Philip II, son of emperor Charles V,” and that refers to only one man, the king Sofonisba served for over a decade. The inscription has been assumed to be inaccurate since she could not have seen Philip as a child. But what if she could imagine it?